The racist

ideology directed towards minorities in America is not a new phenomenon. Prejudiced

attitudes towards American Indians in particular date back at least to colonial

times. In this article, I’ll explore

this phenomenon through a group of advertisements that were produced from the

1880s until around 1920. As diverse as

the ads are, many are guilty of using culturally appropriated themes to sell

their products. Defined as the adoption of specific elements of one culture by

a different cultural group, cultural appropriation embodies the use of ideas,

symbols, artifacts, images, objects, etc. derived from contact between

different cultures. It often implies a

negative view towards the minority culture by the dominant one and is often

culturally insensitive. The examples

presented below are a reflection of the biases and prejudices of the day.

Negative attitudes towards American

Indians continue to be perpetuated in the mass media evidenced recently by the sexy

fashion events produced by Victoria’s Secret where their models disrespectfully

dressed in pseudo American Indian attire that contained appropriated symbols

that are viewed as sacred to many Native people; and repeated calls to

eliminate racist Indian mascots in sports continues to fall on deaf ears.

So why are advertisers so intent on

associating their products with American Indians? Unfortunately, there is no

simple answer to that question. Since the time of first contact, First Nations

people have been under intense pressure to assimilate into mainstream society. By

the turn of the twentieth century, the Indian wars had come to an end and many

Native people were struggling to adapt to a new way of life. Although the

military campaigns were over, a more subtle war over cultural identity was

underway. Evidence of this is reflected

in newspaper and magazine advertisements, as well as in journalistic articles

and state reports where Native people were often referred to in condescending

and disparaging terms (figure 1).  |

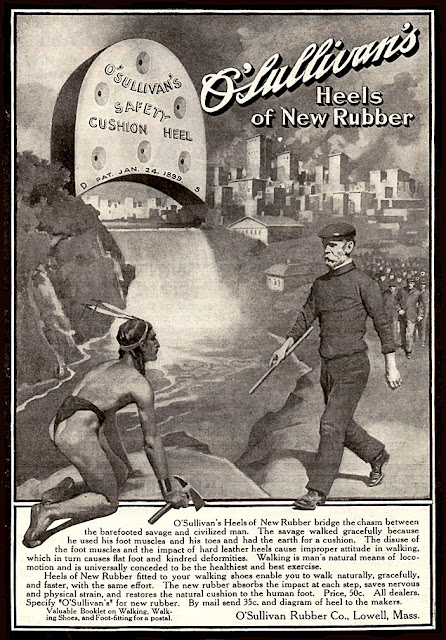

Figure

1 – A 1908 advertisement in Munsey’s

Magazine for O’Sullivan heels. The ad juxtaposes an “uncivilized” Native (who

is referred to as a savage) kneeling before the onslaught of civilization.

|

A case in point is the

January 27, 1888 edition of the Cattaraugus Republican, a newspaper from

Salamanca, New York. It ran an extract from the Annual Report of the Superintendent

of Public Instruction for the State of New York by Andrew S. Draper and in his

concluding remarks, Draper’s prejudice toward the Indians is shamelessly

apparent. He wrote that “there are eight reservations [in New York], covering

more than 125,000 acres of land, as tillable and beautiful as any in the state.

Not an acre in a hundred is cultivated. Upon each reservation there is a tribal

organization which assumes to allot lands and to remove settlers at will, so

that no permanent improvements are possible. In numbers they are increasing

rather than dwindling away. The reservations are nests of uncontrolled vice,

where wedlock is commonly treated with indifference, where superstition reigns

supreme, and where impure ceremonies are practiced by pagans with an attendance

of both sexes and all ages, where there is no law to protect one or punish

another: where the prevailing social and industrial state is one of chronic

barbarism, and which the English language is not known or spoken by the women

and children, and by only part of the men. All this is in the heart of our

orderly Christian state.

In many cases, this practice was used simply for the benefit of the

advertiser and in some cases to lampoon Native people (figure

3).

This state of things cannot go on indefinitely…

The state is undoubtedly bound by treaties formally entered into, but when

treaties perpetuate barbarism and protect vice, they should be broken. These

people are not to be considered as equals; they are unfortunates; they do not

know what is best for themselves; they are the children of the state… treaty

obligations should not forever protect Paganism in saying to Christian

civilization, ‘Thus far only shalt thou go, and no farther.’”

Andre Lopez has demonstrated that In the

United States, “the press has been fortunate enough to be able to obscure its

most blatantly racist opinions beneath the cloud of public ignorance on this

subject. In the area of Native sensitivities, it has only been during the past

several decades, and even then only in the more liberal communities, that

blatant racism toward Native people has simply become less popular, less vogue.

Prior to this… the press dispatched attitudes in its reporting style which

reflected the true attitudes and popular beliefs of the American public. Among

those beliefs was… that Native peoples were ‘savages,’ that they were unclean,

somehow biologically and socially lacking in graces and manners, an inferior

people” (Lopez 1980: xi).

A short yet condescending newspaper article

in the August, 1894 issue of the Syracuse (New York) Standard, titled: A LOT OF

NONESENSE reported that “A great many people drove out to the Onondaga

reservation yesterday afternoon to see the Pagan Indians in council. There was

a pow-wow in the afternoon. The Indians rigged themselves up in all sorts of

grotesque outfits and capered around the Council house for the benefit of the

whites. It was called a religious ceremony.

Missionary Scott of the Episcopal Church

doubts whether the Indians have come together for anything more than a good

time. He doesn’t believe that the chiefs know anything about the doctrines of

Handsome Lake. He himself has never been able to get two similar accounts of

the so-called prophet-teachings. In his opinion, there is more politics than

religion in this council.”

It’s not hard to imagine how Native people

felt and reacted to these characterizations. In writing about the Iroquois in particular,

Lopez says that there were “Indian people who would react so strongly to the

stereotypes that they would become, in culture and behavior, more like white

people than the white people were. It was a case of the oppressed imitating

their oppressors in the (unconscious) hopes of escaping their oppression”

(Lopez 1980: xvii).

Beginning in the nineteenth century and

continuing throughout the 20th century, American Indian themes were

regularly used in print advertising. From about 1890 until World War 1, a

fashionable home-decorating trend was under way that Elizabeth Hutchinson

describes as “the Indian Craze” (Hutchinson 2009). During this period, mainstream

society developed a passion for collecting American Indian art objects and this

might account, in part, why advertisers often used Indian themes to sell their

products. A diverse range of products were

promoted that, for the most part, had no connection at all to American Indians.

Indian themed advertisements for toys, tools, clothing, alcoholic beverages, food

products, toothpaste, bicycles, cameras, automobiles, tobacco, even vacation

trips were used to sell these and a host of other products; virtually no

segment of the commercial marketplace was exempt (figure

2.)

It’s been argued that such representations are actually “a continuing form of colonialism and oppression.” That is, they effectively “shrink an extremely diverse community of over 565 tribes in the United States alone down into one stereotypical image of the plains Indian” (Adrienne Keene, from an online interview in Al Jazeera’s The Stream. Adrienne is a Cherokee from Oklahoma and the author of the Native Appropriations blog). In many instances, the Indian themed advertisements are nothing short of cultural appropriation and additionally, some were unabashedly racist (figure 4).

|

Figure

4 – A Ladies Home

Companion Magazine ad from 1896 for Sapolio, a company that produced soaps and

other cleaning products.

|

Victorians had a sentimentalized view of Indian life derived from prints and magazine articles in which Native people were often inaccurately depicted as still living in quintessential harmony with nature. Indian encampment life was romanticized by some writers, such as a Mademoiselle Rouche, whose account appeared in an 1859 edition of the Lady’s Newspaper (see: Phillips 1998:218–221). Although the camp in her narration was apocryphal, it provided a romantic attachment to an idealized life and advanced the exotic illusion that Native people and their creations were the end product of this pastoral and bucolic existence. Some of the Native attributes that advertisers hoped to associate with their merchandise were naturalness, strength, purity, and that their products were authentically American (figure 5.)

A 1918 advertisement for the United States

Tire Company from Seattle, Washington, has an agile and fit looking Indian

jumping across a fast moving stream towards a tire on the other side. In bold

letters, the ad reads: LITHE, SINEWY, ENDURING. UNITED STATES “ROYAL CORD”

TIRES. Advertisers weren’t shy about appropriating Native themes to bolster

their ad campaigns.

Until about the middle of the nineteenth century, America was still a

rural, agricultural society but with the advent of the industrial age, people began

moving to cities. Life there offered advantages such as better and higher

paying jobs and access to services not available in rural areas but there were

also serious disadvantages. Sanitary conditions in most cities were miserable

to nonexistent and they became unhealthy places to live; many were ravaged by

epidemics such as cholera, influenza and typhoid.

By this time, the character of children, especially boys, was perceived by many

to be imperiled by an effeminate, post frontier urbanism (Deloria 1998:96).

Daniel Carter Beard, a cofounder of the Boy Scouts, believed that Indians

offered patriotic role models for American youth and some businesses echoed

these sentiments in their advertisements. In a 1920 promotion for Indian

bicycles from the Hendee Manufacturing Company, the same company that produced

the Indian motorcycle, the design depicts a boy and his father admiring a

bicycle in a showroom window. The advertising text reads in part; “The Indian

most certainly is the bicycle for every healthy, manly American boy,” and that

it “reminds one of the true-blooded race horse.” It suggests that the use of their

product would ultimately turn a soft and tender child into a real man.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century and until the 1980s,

thousands of magazine advertisements displayed images of Native people or

themes on their pages. These advertisements flourished during the period that

Elizabeth Hutchinson refers to as the “Indian Craze” – 1890 through 1915 (Hutchinson

2009). She describes how American Indian blankets, baskets, rugs, etc. could be

purchased directly from east cost department stores, from Native people

themselves, from agents and a host of other outlets. “Native American art was

seen as a distinctly superior form of decoration, in keeping with the

increasing nationalism and protectionism of the nation at the time. Native

American art allowed people of the United States to combine these nationalist

and colonialist interest, by appropriating the material culture of subjugated

indigenous people as an expression of national aesthetics. They embraced the

fact that Indian art was made out of local material and described its various

forms as a reaction to the national landscape. Most important, critics urged

collectors to buy Native products instead of sending money overseas. As one writer put it (in 1901), ‘Americans

send hundreds of thousands of dollars every year to Germany and Japan for

hampers, scrap baskets, clothes baskets, market baskets, work baskets, fruit,

flower, lunch and candy baskets, - money which, by every right, should be

earned by our needy, capable Indians’” (Hutchinson 2009:26).

A March 28, 1901 advertisement in the New

York Daily Tribune, for the Wanamaker’s Department Store, informed the public

that an Abenaki basket maker and her daughter would be demonstrating their skills

on their premises. There would be a selection of their baskets and other crafts

for sale. Below is the full text of the ad as it ran on that day.

Indian Baskets and Their Makers.

We have an interesting exhibit of these

pretty baskets in our basement store. They have all been made by hand by the

Abanaquis Indians of Maine and Canada. A native Indian woman who speaks such

excellent English that we hesitate to call her a squaw is here making baskets

and other fancy articles. She has her little daughter with her, who is also

quite expert; and has made some baskets which she will show you.

The wigwam is here, and is decorated in

savage style. Interesting to curiosity seekers; and yet the baskets and other

decorative things are very pretty and quite practical. This hint of some of the

articles:

Baskets

are made of swamp ash and sweetgrass.

Price

of Baskets, 10c to $1.75

Birch

Wood Canoes, 30c to $2.50

Bows

and Arrows, 20c to $1.50

Doll

Moccasins, 25c and 50c

Large

Moccasins, $1.50 to $2.50

Indian

Dolls, 40c to $2.25

John

Wanakaker – Formally A.T. Stewart & Co.,

Broadway,

Fourth Avenue, Ninth and Tenth Streets

In her thesis, Hutchinson argues that

policy makers were influenced by the “Indian Craze” and came to understand that

“traditional” American Indian art was worth preserving.

During this period, there were numerous,

well executed advertisements for the Santa Fe Railroad. Their service covered

the West, from Chicago to California and their advertisements advanced the idea

that the Native inhabitants of the southwest lived an idealized and romantic

life. A trip through Indian Country was publicized

as a pleasurable experience into a quaint and mystical world. Indian guides

were hired by the railroad and one ad in particular noted that “As the train

glides across New Mexico, your Zuni guide tells you about the legends of this

romantic land.”

Visitors to the American Southwest were

intrigued with the seemingly less hectic lifestyle of Native people and many

were intrigued by the complex religious beliefs, ceremonies, and especially the

crafts of their skilled artisans. This interest led to opportunities for Native

artisans to sell their creations and for tourists to acquire them (figure 6).

|

Figure

6 – Two well executed advertisements from 1902 for the Santa Fe Railroad.

|

By the turn of the twentieth century,

Indian traders and dealers were sending mail-order catalogs to prospective

clients advertising the availability of the genuine, hand-made Indian goods

they had for sale. Anglo-Americans could also special order Native made items designed

to their liking and to be more harmonious with their home décor. So there was a

transcultural exchange taking place.

Not only had the public at large developed

a passion for collecting American Indian art, but both children and adults

engaged in Indian play of some sort. Images from this period of non-Natives

dressed as Indians and participating in plays, pageants, etc. are common.

Advertisements also offered Indian play outfits for both children and adults (figure 7).

|

Figure

7 – A page from a circa 1920 DeMoulin Brothers fraternal outfit catalog and a 1911

advertisement for Indian play suits from a company called “Little Folks.”

|

Hutchinson identifies this

collecting fever as part of something larger that included the addition of

American Indian objects in museum exhibits, World’s Fairs, and the use of

“indigenous handcrafts as models for non-Native artists exploring formal

abstraction and emerging notions of artistic subjectivity” (Hutchinson 2009). A

cross-cultural interest developed during this period and many advertisements portrayed

Native people in a positive light. Some of the Santa Fe railroad ads in

particular were visually appealing, often showing the local Natives either working

on their craft or displayed with it (figure 8).

|

Figure

8 – This Travel Magazine

advertisement from 1916 was for the Santa Fe Railroad.

|

Not all ads from this period depicted Native people in a positive light.

An 1899 advertisement for the Savage Arms Company of Utica, New York boldly

stated that their rifles “Make Bad Indians Good” (figure

9).

|

Figure

9 – A blatantly racist ad from the May 1899 issue of Cosmopolitan

Magazine playing on the sentiment that the only good Indian was a dead

Indian.

|

Drawing on a theme that was prevalent in

the late nineteenth century that “the only good Indian was a dead Indian,” this

sentiment is usually attributed to General Phil Sheridan. He was a career Army

officer and Union army general during the Civil War. In 1869, Comanche Chief

Tosawi reputedly told Sheridan that he (Tosawi) was a good Indian, to which

Sheridan replied, “The only good Indians I ever saw were dead.” His sentiment

became popular with the general public, and “Indian policy” for the

military. Even Teddy Roosevelt weighed

in on the matter in an 1886 speech: "I suppose I should be ashamed to say

that I take the Western view of the Indian. I don't go so far as to think that

the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every ten

are, and I shouldn't like to inquire too closely into the case of the

tenth." The advertisement in figure 9 is

certainly echoing the sentiment of the time.

Some of the most remarkable and

memorable art of the last 100 years was created

by talented Illustrators who produced work for magazine print

advertisements, i.e. Norman Rockwell, J.C Leyendecker, and Charles Dana Gibson, the

creator of the Gibson Girl. The birth of

modern advertising began in mid-nineteenth century Philadelphia when Volney B.

Palmer created the first advertising agency. He understood that promoting and

selling a product worked best on a regimen of emotion, persuasion and good

sense. Advertising agencies emerged around the time of the industrial

revolution where they were used to help sell products and services. The reason for advertising, after all, was to

make the consumer connect with the brand and become a loyal customer. If there

was a developing “Indian Craze,” advertisers were going to capitalize on it. What follows is a gallery of advertisements

that were produced during this period. They’re not in any particular order but were

selected to explore the range of product advertised and how Native people were

represented in those ads. Bear in mind that this is just a small sampling of

the thousands of products that were promoted using Indian themes.

|

Figure

10 – A Scribner’s Magazine

advertisement from May, 1910 for the Northern Pacific railroad.

|

|

Figure

11 – Two advertisements for the Angelus Player-Piano by Wilcox and White

Company of Meriden, Connecticut; one from 1913 and the other from 1915.

|

|

Figure

12 – An American Cooking Magazine

advertisement from 1915 for Red Wing grape juice. Here the advertisers are

using and Indian theme to suggest the purity of their product.

|

|

Figure

13 –

|

|

Figure

14 – An 1897 advertisement for Pabst Milwaukee Beer that is touted as a

healthful tonic.

|

|

Figure

16 – Another railroad advertisement from the May, 1904 issue of Booklovers Magazine.

|

|

Figure

20 – This curious June, 1900 advertisement from Scribner’s Magazine suggested their product would prevent premature

baldness.

|

|

Figure

21 – This 1901 ad in Harpers Magazine

for the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad used a play on words in featuring

an Indian in a frying pan.

|

|

Figure

22 – A caricature of an Indian is used in this Inland Printers magazine

advertisement from 1917. It advertised Indian Brand gummed papers.

|

|

Figure

23 – A Northern Steamship Co. advertisement that was featured in a 1904 Outlook Magazine advertisement.

|

|

Figure

24 – This November, 1915 advertisement ran in American Carpenter & Builder Magazine. It featured a table saw

from the Oshkosh Manufacturing Company.

|

|

Figure

25 – Another Savage Arms Company advertisement, this one from June, 1901,

employs a double entendre as the Maine guides depicted in the ad were certainly

Wabanaki Natives.

|

|

Figure

26 – There were a number of ads from this company that featured an Indian child

wearing the company’s shirt collars and cuffs. This ad is from an October, 1901

issue of Century Magazine.

|

|

Figure

27 – A 1905 advertisement in Country Life

in America Magazine for Victor Talking Machines, the forerunner to RCA.

|

|

Figure

29 – Cereal ads for corn products often featured American Indians themes like

this ad from the March, 1908 edition of Century

Magazine.

|

|

Figure

31 – Another ad from the April, 1917 issue of The Ladies’ Home Journal also offered non-Native women instructions

in making Indian style baskets.

|

|

Figure

33 – This 1901 McClure’s Magazine

advertisement for the Lozier gas engine compares their motorized product to an

Indian canoe.

|

References Cited:

Deloria, Philip J. Playing Indian. New Haven & London:

Yale University Press. 1998.

Hutchinson, Elizabeth. The Indian Craze. Durham and London:

Duke University Press. 2009.

Keene, Adrienne. From an online interview in Al

Jazeera’s The Stream

Lopez, Andre. Pagans in

Our Midst. Akwesasne Notes, Mohawk Nation, Rooseveltown, New York. 1980.

Phillips, Ruth B. Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native

North American Art from the Northeast, 1700-1900. Seattle: University

of Washington Press. 1999.