During the nineteenth century, the western New York

Haudenosaunee, particularly the Tuscaroras, were on the frontlines of the

world’s most exciting and emerging tourist market. Occasionally on late-nineteenth and

early-twentieth-century beaded bags, but more often on related items of Iroquois

fancy beadwork such as picture frames, pincushions, sewing cases, match

holders, good-luck horseshoes, etc., sentimental inscriptions were written out

in beads. Common phrases were “Think of Me”, “Forget Me Not”, and “Remember Me”

along with numerous variations and many pieces dated in beads. It’s not clear

exactly when this practice began but an Iroquois bag was exhibited in the Across

Borders: Beadwork in Iroquois Life exhibit bearing a beaded 1830 date. You

can see the bag in this blog posting; it’s the earliest piece dated in beads

that I am aware of.

Many other pieces also included the names of the locations

where they were sold, such as “Montreal”, “Saratoga Springs” and “Niagara Falls”.

In this blog posting, I will explore the

origins of the beaded inscription “From Niagara Falls” in Tuscarora work and

why it suddenly appeared in their beadwork around 1860.

Prior to 1860, we

sometimes see a hand-written inscription on an inside flap or on the back of a

piece of beadwork that indicates the item was “From Niagara Falls.” Sometimes a

piece is accompanied by an old note indicating that it was purchased there.

The Revolutionary

War (1775-1783) compelled the curtailment of the Haudenosaunee’s traditional

life style and forced many communities to find new ways to subsist. After the

Revolutionary War, reservations were established in western New York and in southern

Ontario. Each one of these reservations

would subsequently produce souvenirs for the emerging tourist trade at Niagara

Falls. As colonialist incursions increasingly undermined traditional ways of

life, the Iroquois developed survival strategies, the most successful of which was

making articles for sale at Niagara Falls, where tourists flocked to witness

the grandeur of nature. Iroquois artists made souvenirs and also useful

objects, such as moccasins, hats, pincushions, and various types of containers. We

may never know exactly when they began producing beadwork for the souvenir

trade, but the dating of the earliest material suggests it began soon after the

end of the Revolutionary War.

Travelers to the

area were confronted by the presence of the Haudenosaunee and many actually

sought them out. The traditional arts that existed prior to the American

Revolution changed, and in many cases disappeared, to be replaced by the

emergence of hybrid styles of commoditized beadwork that in the early

nineteenth century were sold predominately at Niagara Falls.

One of the

earliest Haudenosaunee souvenir beaded bags that was collected at the Falls is

illustrated in figure 1.

According to a note left by a prior owner, the

bag was acquired in 1794, which seems rather early for this style of purse. It’s

most likely from the first quarter of the nineteenth century as it is stylistically

similar to a bag in the New York State Museum in Albany, that was collected in

1807 (see figure 3.5 in A Cherished Curiosity).

Another early bag was collected in Lewiston, New York near the Tuscarora

Reservation (figure 2).

The earliest published

reference I am familiar with to beadwork being sold at Niagara Falls is found

in the New England Magazine, Number 8, February 1835, pages 91-96. In an

article titled “My Visit to Niagara Falls” by Nathaniel Hawthorne, he writes:

“After

dinner – at which, an unwonted and perverse epicurism detained me longer than

usual – I lighted a cigar and paced the piazza, minutely attentive to the

aspect and business of a very ordinary village. Finally, with reluctant step,

and the feeling of an intruder, I walked towards Goat Island. At the

toll-house, there were further excuses for delaying the inevitable moment. My

signature was required in a huge ledger, containing similar records

innumerable, many of which I read. The skin of a great sturgeon, and other fishes,

beasts, and reptiles; a collection of minerals, such as lie in heaps near the

falls; some Indian moccasins, and other trifles, made of deer-skin and

embroidered with beads;… all attracted me in turn. Out of a number of twisted

sticks, the manufacture of a Tuscarora Indian, I selected one of curled maple,

curiously convoluted, and adorned with the cared images of a snake and a fish.

Using this as my pilgrim’s staff, I crossed the bridge.”

In August of 1843, another article appeared in a western Massachusetts newspaper about the Tuscarora.

In August of 1843, another article appeared in a western Massachusetts newspaper about the Tuscarora.

We find an interesting

letter from a correspondent of the N.Y. American, the following account of a

visit of Mr. Adams, during his late northern tour, to the Indians of the

Tuscarora “reservation.”

“A most agreeable incident

of our visit has been the presence of the illustrious ex-President, John Quincy

Adams. He arrived late on Saturday evening, after a long, rapid and fatiguing

journey, by way of Montreal and Ogdensburg, and yesterday morning, accompanied

by Gen. Peter B. Porter, and other friends, went to the Tuscarora reservation,

and attended the public worship of the Indians—many of whom, before and during

the service, were lying in picturesque groups under the trees about the chapel,

with their broadcloths blankets, their ears, hats, leggings and moccasins

glittering with beads, medals, and other finery. The little papooses were

snugly strapped to flat boards about as long as themselves, with only the head

exposed, encased like little Egyptian mummies, except that they were bandaged

with embroidered scarlet instead of cerements—They were in the laps of the

squaws or suspended on their backs, or leaned up against trees or rocks, much

as you would place an umbrella against the wall or in a corner—They lolled

their little tawny heads about, and with their bright black eyes gazed

wonderingly over the beautiful domains of their fathers.

“In the chapel the sermon

was rendered in to the Indian language, sentence by sentence, by the chief. The

congregation were about as somnolent as white Christians are apt to be; and the

new blue silk shawl, in which (instead of her blanket) a young and beautiful squaw

has enveloped herself, produced about as much “sensation” among the other dark

belles, as any similar splendor would among the paler beauties of a city

congregation. The singing by the Indians was delightful, and I have rarely

heard sweeter and softer voices. After

the services were concluded, the ex-President was desired to address them. When

it was announced that he would do so, the Indians looked and listened with

great intentness. Mr. Adams’s unpremeditated discourse was admirable, and

delivered with much feeling and effect. The chief rendered it, as he had done

the sermon, sentence by sentence, in the Indian language.

“Mr. Adams alluded to his

advanced age, and to this being the first time that he had ever looked upon

their beautiful fields and forest—that he was truly happy to meet them there

and join with them in the worship of our common Parent—reminded them that in

years past he had addressed them from the position which he then occupied in

language at once that of his station and his heart, as “his children”—and that

now, as a private citizen, he heard them in terms of equal warmth and

endearment as his “brethren and sisters.” He alluded with a simple eloquence

which seemed to move the Indians much, to the equal care and love with which God

regards all his children, whether savage or civilized, and to the common

destiny which awaits them hereafter, however various their lot here. He touched

briefly and forcibly on the topics of the sermon which they had heard, and

concluded with a beautiful and touching benediction upon them. Among the elders

of the congregation were several who had

fought at Fort Erie, Chippewa and Lundy’s Land, under General Porter, to whom

they look up with affection and reverence as their steady friend, and as the ‘great

counselor and warrior’” (From: The Pittsfield Sun, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, August 17, 1843, page 2). I would like to thank Grant Wade Jonathan for bringing this article to my attention.

Nineteenth-century

travelers were most likely to find the “cherished curiosities” they were

seeking at Niagara Falls. The best views

of the cataract were from Goat Island, but to get there, an 1839 guide book

informs the traveler that they would first have to cross the bridge to Bath

Island, then “ascend the bank, enter the toll-house, and pay the charge of

twenty-five cents each; which gives the individual the privilege of visiting

the island during his stay at the Falls, or at any time thereafter for the

current year (fig. 2a).

They register their names, and look at the

Indian and other curiosities,” in the bath house that was operated by a Mr.

Jacob, “which are kept there for sale; and generally make some purchases, as

remembrances of the Falls, or for presents to friends or children” (DeVeaux

1839:56). DeVeaux goes on to say that “Niagara Falls has also become a mart for

Indian curiosities. Of the same

gentleman [Mr., Jacob] may be obtained moccasins, worked with beads and

porcupine quills. Indian work pockets, needle cases, war clubs, bark canoes,

maple sugar in fancy boxes ornamented with quills, & c” (DeVeaux 1839:163).

Some uncertainty

remains over the attribution and dating of early Haudenosaunee fancy souvenir

beadwork because of the lack of well-documented examples. It’s often difficult

to attribute tribal identity to a piece because of the meager ethnographic

evidence and the extensive trading that occurred between Native communities.

Additionally, the

Iroquois sometimes wholesaled their work to middlemen, shopkeepers, and to

other Indians; designs and motifs were borrowed and exchanged between Native

communities. Added to this is the movement of pieces by tourists. So extensive

was the trade with the Tuscarora that

"…they were unable to manufacture enough souvenirs to meet

the demand. So they became middle men buying the beaded pouches, moccasins,

baskets, etc., from the Mohawks of Caughnawaga, St. Regis, and Lake of Two

Mountains, from the Senecas on their neighboring reservations in New York

State, from the Iroquois at Six Nations, from the Ottawa, the Algonquin at

River Desert (Maniwaki), and others" (Dodge 1951:4).

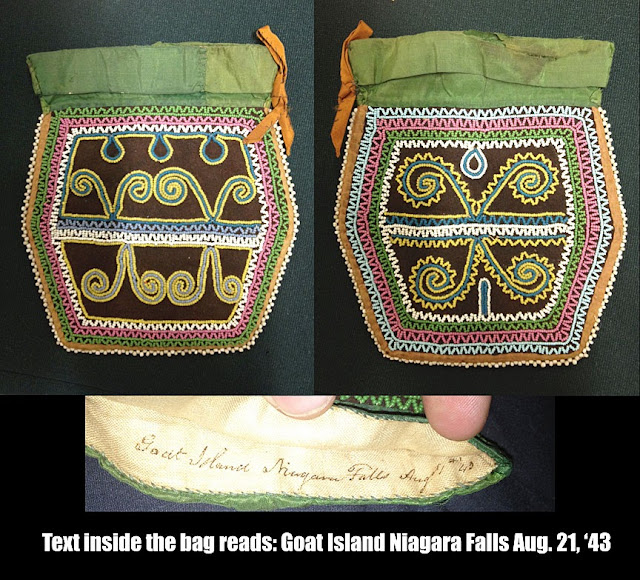

Figures

3 & 4 are two other mid-19th century bags with hand-written inscriptions indicating

that they were acquired at Niagara Falls.

|

Figure 4 – A beaded bag in the Parker style collected at

Niagara Falls in 1846.

|

Sometime

in the early 1840s, a new style of beadwork emerges that likely had its roots

in Niagara Falls, and possibly with the Seneca (See A Cherished Curiosity for

more information about the development of the Niagara Floral Style). Examples

of beaded hats, moccasins, bags (fig 5) and a host of other items were done in

this style which became the predominate beadwork style produced in many

Haudenosaunee communities during the second and third quarters of the 19th

century.

The historical record of attributed examples

points to the fact that these were made in most Iroquois communities, although

the details that allow us to distinguish an example that is say Tuscarora,

Seneca or Mohawk is less clear. For as long as I have been collecting and

researching Iroquois beadwork (almost 30 years), this style has been referred to

by people in the antiques field as the “Niagara Floral Style”. This can lead to

some confusion as some non-Natives think there was a tribe called the Niagara but

there isn’t. The term, as I’ve always understood it, doesn’t refer to a

specific Nation but rather to a style of beadwork that was often sold at the

Falls. Additionally, to add to the

confusion, the fancy beaded picture frames, pincushions, sewing wallets,

good-luck horseshoes, beaded canoes, beaded birds, etc. that the Tuscarora sold

at the Falls beginning in the second half of the nineteenth century, are sometimes

referred to as Niagara beadwork. The Tuscarora and others do not agree with the

use of the term “Niagara beaded” when it applies to their beadwork. They feel it’s

culturally insensitive and if collectors and museums are going to call Mohawk

beadwork by its name, the same should be true of Seneca and Tuscarora beadwork.

They consider the term to be deceiving and inappropriate.

Another style of

beadwork that was sold in Niagara Falls, beginning in the 1850s, was beaded

primarily with crystal beads and usually on a red fabric ground (fig. 6). This

particular piece has a hand-written inscription on the back indicating it was

collected in July, of 1857.

|

Figure 6 – Watch pocket, Tuscarora with the inscription on

the back that it was collected at Niagara Falls in 1857.

|

By

about 1860, another development arose in the beadwork that was produced for

sale to travelers who visited the Falls. Now we begin to see more pieces that

contain dates and sentimental inscriptions, beaded onto the piece itself, and

especially prominent is the beaded addition of the place of purchase, such as “From

Niagara Falls” (figs 7 & 7a).

|

Figure 7a – Detail view of the sewing wallet in figure 7.

|

Like many of the pieces from the 1850s, they were

also embroidered primarily with crystal beads. The sewing wallet in figure 8

has a similar inscription, although on this example it is not beaded onto the

piece but rather appears to be applied in the form of a rubber stamp or printed

onto it.

It also incorporates the use of the term

“present” but this designation appears to have been dropped from pieces produced

after the early 1860s to simply “From Niagara Falls,” “From Niagara,” or

“Niagara Falls.” The sewing wallet in figure 9 is very similar to the one in figure

8 and here we can see “Present From Niagara Falls” and a date of 1862 beaded

onto the piece.

|

Figure 9 – Sewing wallet with the inscription “Present From

Niagara Falls” beaded in metal beads. This piece is also dated 1862 in metal

beads.

|

Why

did “From Niagara Falls” suddenly appear beaded on pieces of Tuscarora work

about this date? Did a traveler request it and the practice stuck? There were

non-Indian made souvenirs sold to tourists in the bazaars at the Falls, many of

which were imported, and some of them included the “From Niagara Falls” cachet

(fig 10). The reason why the Tuscarora started using it about this time is

still unclear although by adding “From Niagara Falls” to their work, the

beadwork may have taken on a new purpose; primarily to distinguish it from the

work of outsiders. Perhaps a shopkeeper suggested its use as travelers wanted a

memento that reminded them of their trip and where they had been. There may

have been other factors that led to its use as well as we shall see below.

|

Figure 10 – Non-Native made clamshell purse with

hand-painted flowers and the “From Niagara Falls” cachet. Second half of the

nineteenth century.

|

The Niagara Falls

scholar, Karen Dubinsky, relates that

“Edward Roper, visiting Niagara for a second time in the

1890s, noted, “There are the same Indians about as of old; they say the squaws

come generally from ‘ould Oirland’ [Ireland].” Many visitors complained about

“Irish Indians” or “Indian curiosities” made in New York or England or France,

or later, of course, Japan), and by the 1890s one of the popular guide book

series edited by Karl Baedeker was warning readers that “the bazaar nuisance [at

Niagara] continues in full force…. Those wishing Indian curiosities should buy

them from the Indians themselves” (Dubinsky 1999:64-65).

The composer

Jacques Offenbach, while on a trip to the Falls in the 1870s, wrote that after

having enjoyed the spectacle of Niagara Falls

“I

crossed the bridge and set foot on Canadian soil. Here, I had been told, I

would see Indians. I expected to find savages, and was surprised to find only

dealers in bric-a-brac. They were hideous, I confess; they looked quite ferocious,

I admit also: but I doubt whether they were genuine Indians. However that may

be, they surrounded me on all sides, offered me bamboos, fans, cigar holders,

and pocket-books of a doubtful taste… Nevertheless, I made a few purchases; but

I verily believe I brought back into France some curiosities which had been

procured at the selling out of some Parisian bazaar” (Offenbach 1875:168).

Mark Twain also complained

about the Indians at the Falls in the 1860s, believing most of the ones he

encountered were Irishmen disguising themselves as Indians for the sole purpose

of selling bogus Indian souvenirs to tourists and he wrote a satirical essay

about it titled “Niagara.”

One of the

reasons travelers came to Niagara Falls in the nineteenth century was to see

Indians (Dubinsky 1999: 60-61). For those making the journey, Niagara

represented a pure and pristine environment, which was seen as healthful and

invigorating but, just as the Falls became a symbol of America, the Indian

became a symbol of the Falls and an icon of this untamed wilderness.

Karen Dubinsky

writes that:

“The passion for colleting Indian ‘curiosities’ also signals

something of the ambivalent relationship between whites and Native people in

the contact zone…. Female beadwork vendors, such as the often-photographed

sisters Delia and Rihsakwad Patterson, proved a great hit, for visitors seemed

as interested in the merchants as the goods” (Dubinski 1999:66).

But

there were other forces at work during this period that could turn a visit to

the Falls into a harrowing and costly experience; hackmen, swindlers and

con-artists of every sort preying on the unsuspected. Most points of interest at

the Falls, such as the Cave of the Winds, The Inclined Railway, the Ferry to

Canada and Prospect Park, crossing the bridges to either the Canadian or

American side, The Whirlpool Rapids, The Burning Spring, Lundy’s Lane Battle

Ground Observatory, and a host of other attractions charged visitors an

admission fee or a toll. In some places, travelers were led to believe

admission was free and only when they tried to leave were they charged a fee –

to the chagrin of many. To complete the Niagara Falls experience, travelers

were not required to visit each point of interest but they were often

intentionally taken there by deceitful hackmen where they had to pay the toll

or admission fee. Hackmen, or carriage drivers, (fig. 11), worked for the hotels,

and other large business establishments at the Falls and they had arrangement

with the owners of many area attractions to bring them visitors.

|

Figure 11 – Circa 1860 ambrotype of a hackman and his

carriage ferrying visitors around the Falls.

|

They would drive them around to the different

sites but what was unknown to most travelers is that the hackmen were actually

paid a commission, usually 50% of the admission fee, to get them there. So

rather than take a visitor directly to their desired destination, the hackmen

had a strong incentive to take them to every other attraction first, to get

their commissions, before taking them to their requested station.

In his 1884 Complete

Tourist Guide to Niagara Falls, David Young wrote, warning visitors that

“[As] it had ever been… swindling has become more systematic

than in former days, and the public will be surprised when they find who are

connected with it. It is gradually driving visitors from the place, and has

given Niagara Falls a name not to be coveted by the poorest hamlet in

Christendom. For instance, a gentleman arrives at Niagara Falls and puts up at

one of the principal hotels and depends upon his Host for directions in

visiting the various points of interest in the vicinity. He naturally expects

reliable information, but the chances are he will be deceived. It may be and

often is the case, that someone in connection with the hotel is connected with

one or more of the points of interest on either or both sides of the river. He

goes to the office and asks for information concerning the points of interest,

and there, only such points as are of in the interest of the hotel or of those

connected with the hotel, are pointed out to him as points of interest visited

by the great multitude, while all other points are represented as not being

worth the time to go and see.”

“Immediately

he is put into a hack, the driver mounts his seat, and the individual has

really commenced his sight-seeing. The driver who knows his business as well as

the pedagogue knows his multiplication table, plies his victim… with marvelous

narrations of the events and occurrences that have taken place at those points

which they intend visiting, thus drawing the man’s mind away from other points

that the driver knows he dare not drive to on pain of INSTANT DISMISSAL. Should

the gentleman mention any other point, he is promptly discouraged, is told that

the place is not worth seeing or that it is not safe to visit, and should he

still insist upon going, the driver would be compelled, point blank, to refuse

to take him, and should the party yet persist in going he would have to walk or

procure another hack” (Young 1884: 3-4).

The hackmen were

not the only ones taking advantage of visitors. Gift shops and bazaars were

notorious for charging foreigners, unfamiliar with the local area, considerably

more than the usual price for goods.

Cigars that cost a cent and a half each are sold for twenty

cents. Lager beer goes up to ten cents a glass; pop the same, and everything

else in proportion. Ornaments that come from England are sold to the stranger

as Table Rock ornaments, and fabulous stories are told of the difficulty

experience in procuring them (Young 1884:16).

Bogus items were

routinely sold as genuine and if a hackman brought a traveler to one of these

shops he would also get a commission on the sale of items his passengers

purchased. Hackmen controlled the lines of business – the shops and attractions

they favored would succeed – others not willing to pay their commissions were

doomed to failure. Throughout all this, the Tuscarora continued producing

exquisite examples of their beadwork. They also sold their work through shops

in Niagara Falls. It’s unclear what sort of arrangements they may have had with

area establishments but a local businessman – perhaps one slighted by a

hackmean – might have suggested the addition of the beaded “From Niagara Falls”

as a way to offer his customers something unusual; a genuine keepsake from

Niagara Falls that confirmed they had actually been there and was made by the

very exotic people that many Victorians had come to see. Since the early

nineteenth century

Native peoples have been woven into the natural history of

Niagara Falls. Along with waterfalls and wax museums, Native people were

established as tourist attractions, extensions of the natural landscape. The

tourist gaze is created by symbols and signs, and thus one’s journey consists

of collecting—visually, through souvenirs or photograph—the appropriate

symbols. And nothing was a more important signifier of North America than the

peoples of the First Nations (Dubinski 1999:61).

As the Niagara

area developed, civic officials were concerned that growth be balanced among

the different sectors of the economy and not centralized on tourism. Focusing on balanced development was a way of

establishing distance from the old days of tourist gouging and by 1919, the

local Chamber of Commerce actually encouraged local manufacturers to advertise that

their products were made in Niagara Falls.

What follows is a gallery of Tuscarora pieces that contain the beaded “From

Niagara Falls” on the work. As we will see later, the Tuscarora were not the

only Native people selling at the Falls and using the “From Niagara Falls” cachet

(figs 12-26).

|

Figure 13 – A Tuscarora barrel purse decorated with an owl

and a squirrel, themes often seen on Tuscarora beadwork. Last quarter of the

nineteenth century.

|

|

Figure 14 – Two Tuscarora beaded boots with the From Niagara

Falls cachet. Circa 1900.

|

|

Figure 15 – Two Tuscarora sewing wallets. Their similarity

suggests that they were likely made by the same person. Circa 1900.

|

|

Figure 16 – Tuscarora barrel purse. Last quarter of the

nineteenth century. Birds are prominent on many of the pieces from this period.

|

|

Figure 18 – A group of six Tuscarora sewing wallets

decorated with crystal beads. 1860s-1880s.

|

|

Figure 19 – Two Tuscarora sewing wallets decorated with

crystal beads. 1860s-1880s.

|

|

Figure 20 – A Tuscarora beaded bird dated 1899.

|

|

Figure 21 – An exceptional “Good Luck” horseshoe, possibly Mohawk,

and decorated mostly in amber colored beads - dated 1905.

|

|

Figure 22 – Beaded picture frame, Tuscarora with bird and

leaf motifs. Circa 1900.

|

|

Figure 23 – Beaded picture frame, Tuscarora with bird, leaf

and birds nest motifs. Circa 1900.

|

|

Figure 24 – Beaded picture frame, Tuscarora with bird and

leaf motifs. Circa 1900.

|

|

Figure 25 – Beaded picture frame, Tuscarora with bird and

leaf motifs. Circa 1900.

|

|

Figure 26 – Beaded bag with bird motif. 1900-1910.

|

By 1900, some

Tuscaroras were objecting to the competition they were getting from the Mohawks.

An article published in The Niagara Falls Gazette in July of 1900, reported

that:

“[T]wo squaws have come to Niagara from Montreal, Quebec,

says the local correspondent of the Buffalo Commercial, and have taken up a

stand in the park [Prospect Park] close beside the faithful Tuscarora women. Of

course the latter object, but they have so far said little. The Canadian

squaws, it is said, brought five big trunks of work with them this season, and

they have already announced that next year, Pan-American year, they intend to be

on deck May first.

The Tuscarora squaws cannot see why the white man’s law does

not protect them, as well as the products of the whites. Furthermore the

Tuscaroras point out that years ago Tuscaroras were faithful to the Stars and

Stripes … [a reference to their participation in the War of 1812 for the

American cause.] People who learned of the situation in the park yesterday

plainly stated that they thought the Montreal squaws should be asked to retire

to Victoria Park … [on the Canadian side.] Public sentiment is that the

Tuscarora should be undisturbed by foreign competition” (Niagara Falls Gazette

July 28, 1900:6).

The

Mohawks were also adding the “From Niagara Falls” cachet to some of their work

(figs 27 & 28).

|

Figure 27 – Mohawk box purse with the From Niagara Falls

cachet. 1890s-1910.

|

|

Figure 28 – Mohawk beaded boot with the From Niagara Falls

cachet. Circa 1900.

|

There was also the Six Nations Indian Store

located at the foot of the bridge that led to Bath and Goat Islands (fig 29) and

they, like many of the local bazaars and gift shops, carried work from Nations

other than the Tuscarora. The Tuscarora had the exclusive right to sell on Goat

Island, but elsewhere at the Falls, especially in the shops, there was work

available from a host of diverse Indian Nations. In 1843, Theodore Hulett published

a guidebook to the Falls titled Every Man His Own Guide to the Falls of Niagara,

or the Whole Story in a Few Words, to Which is Added a Chronological Table

Containing the Principal Events of the Late War Between the United States and

Great Britain; Third Edition, Faxon & Co., Buffalo, and it gives a detailed

list of the Indian Nations that were supplying his shop with work. There is

also the possibility that Pawnee Bill, the Wild West showman, hired Plains

Indians to produce so-called Iroquois whimsies that were purported to be sold

in shops at Niagara Falls. This link will take you to a blog posting I did onthat some time ago.

The

Tuscarora continued to make pieces throughout the twentieth century (figs 30-39)

that were embellished with the “From Niagara Falls” cachet.

|

Figure 30 – Beaded boot with bird motif. It appears to be

dated 1911 although it should be 1941 as there are some missing beads on that

digit. Tuscarora.

|

|

Figure 31 – Two Tuscarora beaded boots, dated 1900 and 1906.

Their similarity suggests that they might have been produced by the same maker.

|

|

Figure 33 – Beaded Tuscarora purse dated 1939.

|

|

Figure 34 – Beaded heart-shaped pincushion, Tuscarora, dated

1937.

|

|

Figure 35 – A beautiful Tuscarora beaded bag with a bird

motifs on the both the front and back. Dated 1939.

|

|

Figure 36 – Beaded Tuscarora boot with an animal motif.

Dated 1932.

|

|

Figure 37 – Three Tuscarora beaded boots dated 1928, 1981

and 2000.

|

|

| Figure 38 – Three Tuscarora beaded pincushions from the 1960s |

|

Figure 39 – Beaded pincushion by Tuscarora artist Grant

Jonathan. 2009.

|

Rosemary Hill (fig 40), one of the foremost

beadwork artist and teachers at Tuscorara recalled a conversation with her

mother telling her of a woman named Viola Russell who lived on the reservation.

This would have been in the 1930s and early 1940s.

“Viola was an elderly woman at that time and her

and her husband would go up to the park [Prospect Park] at Niagara Falls and

sell the beadwork,” relates Rosemary. “The beadwork she sold there was from four

different Tuscarora women. One was my great-grandmother Delilah Bissell, on

my mother’s side. My great-grandmother also had a bark stand at end of her

driveway where she sold her beadwork on the reservation. My mother said

different people went to help Viola out and sometimes Viola’s husband would go.

I know Viola was Tuscarora but I’m not sure about her husband. My mother

said they would go by horse and buggy and sometimes stay with friends or

rent a hotel room. Viola ran the show,” says Rosie. She also said that Viola

didn’t buy the items she acquired from the Tuscarora women but did take a small

commission on the beadwork that she sold.

Rosemary also

recalled another point that is of interest here. “In the 1970s, there was a

shop in Niagara Falls that was selling Tuscarora beadwork and the shop owner

asked my friend, Penny Hudson, to re-date old beaded pieces that he had in his

shop, you know with beads. He told her his person who was doing it had moved,

and he needed someone to take over the task, but Penny refused.” Why this shop

owner felt it necessary to re-date older pieces is unclear but this brings the

dating of some twentieth century pieces into question.

For Tuscarora

artists, beadwork was a form of artistic, spiritual, and cultural expression

and their designs recorded the workings of their spirit. Beyond their intrinsic

beauty, the beadwork has a value as a medium through which a living tradition

was maintained. The art survives, and the traditions continue as a testament to

the beauty of the human spirit, exemplified by their craft.

I would like to thank

Grant Jonathan at Tuscarora for allowing me to use images of some of his old

pieces in this blog posting.

|

If you have an interest in Northeast Woodland beadwork you

might find my book of interest. Titled: A Cherished Curiosity: TheSouvenir Beaded Bag in Historic Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Art by GerryBiron.

Published in 2012. This is a brand new, hard cover book with dust

jacket. 184 pages and profusely illustrated. 8.5 x 11 inches. ISBN

978-0-9785414-1-5.

Since the early nineteenth century,

Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) beaded bags have been admired and cherished by

travelers to Niagara Falls and other tourist destinations for their aesthetic

beauty, detailed artistry, and the creative spirit of their makers. A

long neglected and misunderstood area of American Indian artistry,

"souvenir" art as it's come to be called, played a crucial role in

the subsistence of many Indian families during the nineteenth century. This

lavishly illustrated history examines these bags – the most extensively

produced dress accessory made by the Haudenosaunee – along with the historical

development of beadworking both as an art form and as a subsistence practice

for Native women.

In this book, the

beadwork is considered in the context of art, fashion, and the tourist economy

of the nineteenth century. Illustrated with over one hundred and fifty of the

most important – and exquisite – examples of these bags, along with a unique

collection of historical photographs of the bags in their original context,

this book provides essential reading for collectors and researchers of this

little understood area of American Indian art.

|

REFERENCES CITED

Across Borders: Beadwork in Iroquois Life exhibit was a

traveling exhibition of Haudenosaunee beadwork organized and circulated by the

McCord Museum of Canadian History, in partnership with the Castellani Art

Museum of Niagara University, and the Iroquois communities of Kahnawake and

Tuscarora. It opened at the McCord in June, 1999, and travelled to

several other venues until February, 2003.

Biron, Gerry

A Cherished Curiosity: The Souvenir Beaded Bag in Historic

Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Art. 2012.

DeVeaux, S.

The Falls of Niagara or Tourist’s Guide to this Wonder of

Nature, William B. Hayden, Buffalo. The Press of Thomas & Co. 1839.

Dodge, Ernest S.

“Some Thoughts on the Historic Art of the Indians of

Northeastern North American,” Massachusetts Archaeological Society Bulletin,

13, vol. 1, 1951.

Dubinsky, Karen

The Second Greatest Disappointment: Honeymooning and Tourism

at Niagara Falls. Published by Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New

Jersey. 1999.

Offenbach, Jacques

Offenbach in America. Notes of a Travelling Musician. New

York: G. W. Carleton & Co., Publishers. Paris: C. Levy. 1875

Young, David

The Humbugs of Niagara Falls Exposed With a Complete Tourist

Guide, Giving Hints That Will Enable the Visitor to Avoid Imposition. Likely

published by the author. Suspension Bridge, New York. 1884.